ZMapp and the fight against Ebola

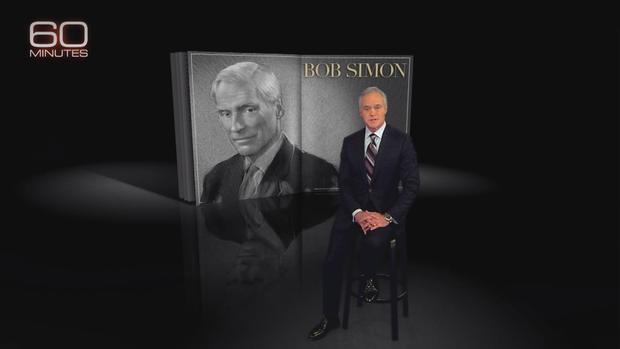

We begin tonight with a story by Bob Simon our colleague and friend, whom we lost this past Wednesday in a tragic car accident. In a 47-year career, reporting from every corner of the globe, Bob set the standard for CBS News.

On Wednesday evening, Bob finished a story intended for this broadcast tonight. It's especially fitting that the producer was his daughter Tanya, a veteran producer at 60 Minutes, who from time to time worked with her dad.

We thought the best way to pay tribute -- and what Bob would have wanted -- would be to put his story on the air in his own words, beginning right here.

The worst Ebola outbreak on record has killed 9,000 in West Africa. But all it took was a few Ebola patients in the United States to show how unprepared we were here, particularly because there weren't any approved vaccines or drugs available to fight the disease.

Now, more than a year after the epidemic hit, clinical trials are at last underway in West Africa. One of the drugs to be tested is called ZMapp and it was used last year to treat nine patients. Only nine because that's all the ZMapp there was at the time...hardly enough to make a dent in the epidemic. So the question now is: Will we be prepared for the next one?

Now, Bob Simon.

The following script is from "ZMapp" which aired on Feb. 15, 2015. Bob Simon is the correspondent. Tanya Simon, producer.

This is the front line in the war against Ebola -- Canada's national microbiology lab on the desolate prairie in Manitoba. It's a good place to experiment with viruses because inside are some of the most dangerous in the world which is why Dr. Gary Kobinger -- who has spent a decade here trying to find the cure for Ebola -- has to seal himself inside layers of protection before getting to work.

One pair of gloves isn't enough.

Kobinger's suit has to be hooked up to oxygen. He could be an astronaut. The door to the lab is sealed as if it were in a submarine and the air is changed 15 times an hour. It takes up to a year of training before anyone is allowed inside so we had to interview Kobinger behind bulletproof glass.

Bob Simon: What are you working on today?

Gary Kobinger: I'm going to do some infection with Ebola because we're trying to improve the treatment we have developed.

The treatment he helped develop here is ZMapp -- widely believed to be the most promising drug candidate to combat the Ebola virus, which is stored in this tank at minus 320 degrees.

Gary Kobinger: So this is how it looks and what it is.

It doesn't look like much, but the virus in that vial could kill thousands.

Bob Simon: Of all the viruses you have in here is Ebola number one? Is it the most dangerous?

Gary Kobinger: Yeah. It is one of the most aggressive, if not the most aggressive.

That's because of how quickly it takes over the body as Dr. Kent Brantly learned last summer. A medical missionary who was treating Ebola patients in Liberia, he was the first American to come down with the disease. And there was very little that could be done to help him.

Bob Simon: Did you know at the time that there were any Ebola drugs being experimented with?

Kent Brantly: Personally I didn't know anything about what was being done in the world of research in Ebola. I figured it was a forgotten disease that drug companies weren't interested in working on.

He had never heard of ZMapp - and didn't know that Gary Kobinger had brought a small amount to the neighboring country of Sierra Leone to see if it could withstand heat and travel. Kobinger never expected to put it to use until word got to him that Brantly wanted the drug. ZMapp had cured monkeys but no human had ever taken it.

Bob Simon: You knew it was experimental. You knew it had never been tested on a human being. Did you have any hesitation or did you figure it's the only shot I've got?

Kent Brantly: I was dying. I was actively dying. So we thought this drug is possibly gonna help.

Bob Simon: You were both a patient and a guinea pig.

Kent Brantly: I have gone from being physician to patient to lab rat.

Bob Simon: After you took the ZMapp did you start feeling better very quickly?

Kent Brantly: Actually my body began to shake and shiver violently and my breathing got worse.

Bob Simon: And you remember that?

Kent Brantly: I remember the people around me praying over me but after that first hour, my breathing improved, the shaking stopped. After two or three hours of receiving the drug, I actually was able to get up and walk to the bathroom. Something I had not done in more than a day and a half.

It's impossible to say what role ZMapp played in Brantly's recovery because he had also received an experimental blood transfusion and first-rate medical care in the United States. Still, after his story got out there was a mad scramble for the eight antidotes that remained of what was being called a miracle drug.

Bob Simon: So putting things in the simplest possible terms, you have invented a cure for Ebola?

Gary Kobinger: Ah, we hope.

Bob Simon: But you've done experiments?

Gary Kobinger: I know it works. I am--I don't need to convince--

Bob Simon: You know it works? Know it works--

Gary Kobinger: Guarantee that it works. I will take it in a flash myself if I get Ebola. But to really make this make this a real scientific fact it needs what is called a randomized trial...

But before any kind of trial could begin, supplies of ZMapp ran out. Now, more than a year after the outbreak hit, just enough is finally being produced for a small clinical trial in Liberia that could start as soon as next week.

If West African lives are to be saved, salvation may well come from Western Kentucky...from these nondescript greenhouses in Owensboro. Their product? A plant usually more associated with destroying lives than with saving them. Tobacco.

This is where the science is turned into a product...where ZMapp is manufactured in row after row of this odd-looking variety of tobacco.

Bob Simon: Can I smoke it? Can I chew it?

Hugh Haydon: I wouldn't recommend that.

Bob Simon: But it's different?

Hugh Haydon: It's very different.

Hugh Haydon is the president of Kentucky Bioprocessing, which was recently bought by cigarette giant Reynolds American.

Bob Simon: When you say tobacco to most people today it suggests cancer and emphysema, heart failure, death?

Hugh Haydon: No question. There's a bit of irony.

Bob Simon: Tobacco is known in our culture as a killer?

Hugh Haydon: There's clearly a bit of irony there. But again there are good things that can be done with it. And that's our objective here.

But ZMapp isn't easy to produce. It takes six weeks. The tobacco plants first have to be grown for 24 days. Then they're immersed in a liquid containing a gene that tells them to make special antibodies, which help the immune system fight viruses, in this case Ebola. As the plants grow, they copy those antibodies over and over again.

Bob Simon: A Xerox machine for antibodies?

Hugh Haydon: That's essentially what it does. It makes it over and over and over again.

The leaves are then ground up into a liquid which looks like a juice you'd buy at a health food store. Since ZMapp is made up of three different antibodies...the process has to be repeated three times using 6,000 pounds of new tobacco plants. And the yield?

Bob Simon: How much ZMapp will you get out of three tables like this? How many people can you cure of Ebola if it works?

Hugh Haydon: It would be dozens best case. It--

Bob Simon: Dozens?

Hugh Haydon: Dozens.

Bob Simon: Which is not very much.

Not very much? Dozens of cures when 9,000 people died in this epidemic? Sounds like using a bottle of water to put out a forest fire.

Hugh Haydon: Lotta work to do in terms of scaling this process if in fact this does become a verified treatment for Ebola.

But the question now is why did we have so little of the drug when the epidemic broke out and so little of it today? That's when it helps to go back 12 years to when the basic idea for ZMapp came about at this miniscule company in San Diego. Mapp Biopharmaceutical has a work force of nine. Its founders Larry Zeitlin and Kevin Whaley -- who recently teamed up with Canadian virologist Gary Kobinger -- could only ever interest one investor in their drug: the U.S. government...which has been funding them ever since.

Bob Simon: You've sort of been a science company on the dole.

Larry Zeitlin: For the most part, yes.

Kevin Whaley: You can say that.

Mapp Bio started out with very modest grants but managed to hobble along. Then, in 2011, the Pentagon expressed interest but didn't give the company any cash or contract for another two years.

Bob Simon: The minute you're working with the government, you're dealing with bureaucracy, you're dealing with time lags, you're dealing with rigidity, you're dealing with a slow pace. Why didn't you go the venture capital route?

Kevin Whaley: These are the kinda projects that venture capitalists are not enthusiastic about because they don't have a near return on investment.

Bob Simon: So we really needed the government on this one?

Kevin Whaley: We certainly did.

The government started funding companies like Mapp Bio long before the Ebola outbreak. After 9/11 and the anthrax attacks, President George W. Bush set aside billions of dollars for the acquisition of medical countermeasures against roughly a dozen radiological, nuclear, chemical and biological threats - including Ebola. The Soviets and a Japanese cult had tried to weaponize it. And in 2006, it became the job of a little known government agency to develop the most promising of those antidotes - of which ZMapp is one. It's called the Biomedical Advanced Research and Development Authority, or BARDA. And it is in effect the government's very own emergency pharmaceutical company.

Dr. Robin Robinson heads BARDA.

Bob Simon: This is the emergency medical cabinet.

Dr. Robin Robinson: That's correct.

His cabinet is an exhibit of the dangers which have already been conquered - among them, vaccines for smallpox and anthrax: drugs for botulism, radiation sickness...

Bob Simon: You still have room in the cabinet. What would you like to see

in here that is not here yet?

Robin Robinson: Oh I hope that we actually have Ebola vaccines and therapeutics like ZMapp on the shelf.

Bob Simon: How soon do you think we'll see 'em there?

Robin Robinson: I hope they're there in the next year.

But that might be optimistic. Drug development takes a lot of time and costs a lot of money, and BARDA has already spent $25 million trying to fast-track ZMapp. And to increase production, it has called on government-funded manufacturing centers that were established to make drugs and vaccines quickly in case of an emergency, like the Ebola epidemic. But months have gone by and they haven't produced a single dose of ZMapp.

Bob Simon: Aren't these facilities supposed to be quick, flexible and nimble at the same time?

Robin Robinson: They are supposed to be nimble and quick in what they do but any bureaucracy has its challenges. And certainly we can always improve on that and we always look to do that in fact.

BARDA is now looking for other ways to make ZMapp.

Dr. Robert Kadlec, President Bush's point man on bio defense, says no matter who you blame, it should never have come to this -- rushing to get ready when an epidemic is in full swing.

Bob Simon: Ebola has been on the radar since '76. Drugs and vaccines are still in development. None are in the market. So why haven't they been developed?

Robert Kadlec: Well-- and that's-- that's the issue, is whether we're spending enough resources to bring these forward and in a way that is commensurate with the perceived risk.

Kadlec, who helped write the legislation creating BARDA, argues it never got the budget for drug development it needed to adequately prepare the country for Ebola or for many of the other agents the government says threaten us.

Bob Simon: Are we prepared for anthrax?

Bob Kadlec: Do we have medical countermeasures for anthrax? Yes.

Bob Simon: Smallpox?

Bob Kadlec: Yes.

Bob Simon: Marburg virus?

Bob Kadlec: No.

Bob Simon: Plague?

Bob Kadlec: Not quite ready for primetime.

Bob Simon: The fallout from a radiological or nuclear attack?

Bob Kadlec: Something like Fukushima if it were to happen today, I think we'd be scrambling.

Bob Simon: Chemical attack?

Bob Kadlec: No, in some ways we were prepared, and I'd say less so today than we were then.

Bob Simon: In terms of the accumulation of your responses, it doesn't (LAUGH) sound very good, does it?

Bob Kadlec: It's not very promising. And again, I think the Ebola crisis offers the opportunity to highlight to the American public and to policymakers both in Congress and the White House that we can do better on this. We must do better on this. And if there's any other requirement for a reminder, Ebola has served that purpose.