A Few Good Women

The following is a script from "A Few Good Women" which aired on March 15, 2015. David Martin is the correspondent. Mary Walsh, producer.

Remember that old recruiting ad the Marines are "...looking for a few good men?" Well, now they're looking for a few good women as well. The Armed Services have been ordered to open all their ground combat units to women by the end of this year - or else give the secretary of defense a good reason why not.

For the Marines that means accepting female volunteers into their Infantry Officer School to see if they can make it through the grueling three-month course. You would expect the training to be tough, but we had no idea how tough until we saw it. The Marines have kept most of what happens in that course secret so anyone going through it doesn't know what to expect. But they opened it up for us so you could see what it takes to become a Marine infantry officer - male or female it doesn't matter because the demands are the same. Can women do it? Take a look and judge for yourself.

Marine second lieutenants charging into battle on their knees, this drill comes two weeks into the 86-day Infantry Officers Course and it's unlike any training we've ever seen. They're on their knees to slow things down enough so as not to cause serious injury. It looks almost prehistoric but Marine General George Smith says it's what combat's all about.

George Smith: We're talking about actively seeking out and locating and closing with, and then destroying the enemy.

General Smith is in charge of an experiment that would put women into the middle of that scrum which until now has been entirely a man's arena.

Second Lieutenant Melissa Cooling wants to be one of those women. But before she can start infantry training she has to pass what's known as the combat endurance test: a 14-hour marathon of physical pain and mental stress which includes everything from basic pull-ups to land navigation and an obstacle course -- all of that spread out over 16 miles. She knows she's facing longer odds than any of the men here. In the last two years, 20 women have gone before her -- and only one has passed the test.

David Martin: You knew what the odds were.

Melissa Cooling: If you look at the odds all the time, you're never gonna achieve anything.

"Yeah, that's one of the myths that's out there, 'Women can't do pull-ups,' but we have it on video now. We can do 'em."

David Martin: So it didn't bother you that in all the previous classes exactly one woman had made it through that first day?

Melissa Cooling: No, it doesn't bother me because she's not me so, and none of the other women are me. I've tried not to think about it as "well, I'm a girl and I'm going to perform like all the other girls." I just try and focus on performing like Melissa.

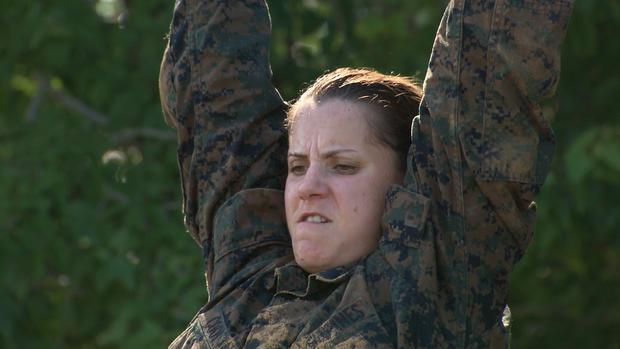

At 5-foot-2, Cooling is shoulder-high to the men, but she's a born competitor -- most recently as a triathlete. She also happens to have a degree in biomedical engineering and a brother who preceded her into the Marine Corps. She is one of five women starting out on this day's combat endurance test but the only one who would let us identify her. Cooling may have to climb to get to the pull-up bar. But once there, she can gut 'em out.

David Martin: Pull-ups are supposed to be the, the bugaboo of, of all women because of upper body strength.

Melissa Cooling: Yeah, that's one of the myths that's out there, "Women can't do pull-ups," but we have it on video now. We can do 'em.

But can they perform all the tasks required of an infantry officer? That's the question General Smith is trying to answer.

"...The issue is the realities of combat aren't going to change based on gender. The enemy doesn't care whether you're a male or female."

George Smith: This is the most physically demanding job-- if you will, in our, in our United States Marine Corps.

David Martin: Does size matter?

George Smith: I think size does matter, especially when you're talking about the ability to march under load.

David Martin: How much does a Marine carry when he's got his combat load on?

George Smith: Well, it's mission-dependent, but I will tell you that it very likely exceeds 100 pounds, and probably gets up above 130 pounds in some cases.

That's more than Cooling weighs, but there are no allowances for size.

George Smith: We could make the bars lower, David, but that's really not the issue. The issue is the realities of combat aren't going to change based on gender. The enemy doesn't care whether you're a male or female.

And neither does the weather. With temperatures in the upper 90s some of the men are dropping from the heat. This combat endurance test is taking place on the hottest day of the summer and for Cooling it's made worse by injury.

Melissa Cooling: I rolled my ankle at the very (laugh) at the very beginning. It was, it definitely stunk.

David Martin: So you just ignored it?

Melissa Cooling: Yep. And you just ignore it and you keep moving.

Others are fighting muscle cramps. But the most difficult part of the test for everyone is the mental challenge of making good decisions despite physical exhaustion. They're not allowed to speak to each other and never know what's coming next - a written exam or a 25-foot rope climb.

George Smith: Fundamental to that course is that sense of uncertainty much like combat.

David Martin: Do they know what they have to do to make it through that first day of the combat endurance test?

George Smith: They don't.

David Martin: So how do they know how well they're doin'?

George Smith: They don't. That's part of the uncertainty

They don't even know how much time they have - which makes stopping long enough to eat - or drink - a calculated risk.

Melissa Cooling: I made some poor decisions by not eating more during the test.

David Martin: And that's part of the test.

Melissa Cooling: That was the biggest part of the test that day, for a lot of people because I know there were a lot of guys in my group that are PT studs and they went down with heat cases and cramps and whatever else because they weren't eating enough.

For most Marines - and especially the women - the make-or-break point in the combat endurance test is the obstacle course. Some of the men are big enough and strong enough to sail through it -- others are struggling.

Melissa Cooling gets off to a good start.

Melissa Cooling: I just looked up at it and I was like, "All right, I'm definitely gonna get this, this is mine." And I made it mine. And I did a little happy dance in my head.

But her strength is giving out - and each obstacle seems more daunting than the last. She has to will herself up and over.

Melissa Cooling: Well, I stared at it for probably a solid minute, you know, workin' up some courage to just go for it.

She finally gets her legs up. But then she comes to the toughest obstacle -- that 25-foot rope.

Melissa Cooling: I was a little nervous about the rope because there is a part of it too that's your grip strength.

She gets half-way up - but can go no higher.

Melissa Cooling: So, my first thought was, "Oh, crap." So, I tried to grab onto the rope so it didn't hurt when I fell. And then I looked up. And when you look up after you fall, it looks like it's a million-foot rope after that.

David Martin: How many more times did you try to get up?

Melissa Cooling: I think there were two more times and that was it.

Starting before dawn, we hiked all 16 miles of the combat endurance test with Major George Flynn. By the end of the day, 20 men had dropped out.

David Martin: And how did the women do?

George Flynn: They pushed themselves. Always saw a max effort. And-- they hung in there.

David Martin: But did any of them make it through?

George Flynn: No, they did not.

That's the combat endurance test at Quantco, Virginia.

[Sergeant: Where's our first victim! Where's our first victim!]

We also traveled to Camp Lejeune in North Carolina to see another experiment the Marines are conducting -- this time on the enlisted side.

Female privates straight out of boot camp are now given the chance to volunteer for the enlisted infantry course.

Nisa Jovell: That's the chance of a lifetime. And if I know I can physically make those requirements and get myself there, I thought, "Why not?"

Nisa Jovell is a powerful enough athlete that she tried out for her high school football team but was not allowed to play. Judging how she handles the obstacle course, you'd have to say that school missed a bet.

David Martin: You pretty much aced it.

Nisa Jovell: Thank you sir.

David Martin: And you were just muscling it through.

Nisa Jovell: (laugh) I was.

David Martin: And then you get to the end and you gotta go up that rope.

Nisa Jovell: Yep. Muscled that too.

Jovell is one of 122 women who have made it through the enlisted course.

[Nisa Jovell: Private Jovell, 2nd Platoon...

Instructor: Bragging rights, right there. Let's go.]

That's a 34 percent success rate compared to zero for the female officers. But the enlisted course is not as demanding -- for one thing Nisa Jovell didn't have to climb that rope with her pack on -- the way Melissa Cooling did.

David Martin: Now you've been through this training, what's your own opinion about whether women can serve in the infantry?

Nisa Jovell: My opinion would be that it would be pretty difficult for them. We're just, unfortunately physically, we are not built for it. And I'm not saying that we can't do it, what they do. But our body structure is different.

David Martin: So what is it really, physically that you think?

Nisa Jovell: Honestly, it was really just carrying a lot of weight. And learning how to move as fast as you can with it.

David Martin: It's what? Bone density that wears you down over time?

Nisa Jovell: It's mainly hips that affect us.

David Martin: Hips?

Nisa Jovell: For females, yes.

David Martin: How does that play out on a 15K or a 20K?

Nisa Jovell: We had to learn how to put on the pack a certain way to like -- relieve the stress off of our hip, so the hip problem is definitely a big deal.

Back at Quantico, the second lieutenants who made it through the combat endurance test - all of them men - are now two weeks into the 86-day Infantry Officer Course.

By now Major Scott Cuomo says every one of them has suffered some kind of injury.

Scott Cuomo: There's not a guy here right now that's not hurting in some way shape or form.

David Martin: Well, you can see it.

Scott Cuomo: One of them, I think broke his nose last Friday. Nobody cares.

David Martin: Is he going to fight today?

Scott Cuomo: Nobody cares.

David Martin: How would a woman do in there?

Scott Cuomo: I don't know sir. We'll see. I mean she, if she comes to this course and gets to this point, she'll be treated just like the men are, so we'll see.

We wanted to see what it takes to get through the rest of the course - so we flew into the mountains of the Mojave Desert in California for the final and toughest part. Eighty-five Marines started out two and a half months ago. Fifty-nine are left and they are 15 days from graduation. All of them are men but we're here to see what females would have to endure taking this final exam - Marine style.

The packs weigh 115 pounds -- not just weapons and ammunition but all the food and water the Marines will need to get them up - and back down -- the steep mountain ridges. We're doing our best to keep up with them but we're not carrying anything close to the loads they're hauling. There are no trails up here and no relief from temperatures that hit a high of 110 degrees.

Nicholas Boire, nicknamed "Animal" - has already been voted best Marine in the course. But even he is almost done in.

Nicholas Boire: Today was real tough sir. The climate change really shocks the body and you're just sucking down water. When you've got a limited amount of it, it really, really beats you down sir.

But as the Marines like to say - nobody cares if you're tired and beaten down.

Somewhere up here there's an opposition force waiting to ambush them.

You would expect to find rattlesnakes in a place like this - but bees? They were a relentless enemy -- going after any drop of moisture they could find on the Marines. They only sting if you swat them but it's hard to resist the urge.

Sunset brings relief from the heat and the bees - and a chance to sleep if you can find a level patch of ground.

When the sun comes up it's time for a shave and a quick meal before there's another ridge to climb and more opposition forces to outmaneuver. You can measure the toll the relentless pace of the 86-day course has taken on 2nd lieutenant Zachary Barbero.

David Martin: How big are you?

Zachary Barbero: Six feet two inches, sir. And about 170 pounds now, sir.

David Martin: 170 pounds now. What were you when you started?

Zachary Barbero: When I started I would say I was around 200 pounds sir.

David Martin: You've lost 30 pounds?

Zachary Barbero: Just about sir.

The Marines must decide by the end of this year whether women should serve in the infantry - that leaves just nine months for female Marines to prove they can make it through the infantry officer course.

David Martin: Would you change anything in that infantry officer course if you found that there was just one-- one thing you could do that-- to greater assure women getting through?

George Smith: David, I think the infantry officer course is designed just right. You look around the globe today. The world is only getting messier and more complex. So we've got it right at the infantry officer course.