Landing site selected for comet mission

After detailed analyses of photos and data collected by Europe's Rosetta spacecraft, mission planners have selected a landing site on the comet 67P/Churyumov-Gerasimenko. It's the spot where a small spacecraft known as Philae will descend to the surface in November, project officials announced Monday.

Rosetta, carrying the Philae lander bolted to its side, caught up with the comet on Aug. 6 after a 10-year, 3.7-billion-mile journey. It is now flying alongside the comet as it falls into the inner solar system, giving Rosetta's instruments a ringside seat as the icy relic comes to life in the warmth of the sun.

If all goes well, Rosetta will release Philae on Nov. 11 for a seven-hour descent to the comet's surface. The 220-pound solar-powered lander is equipped with 10 compact instruments, including a high-resolution imager, gas and dust analyzers and a drill that will collect samples up to eight inches below the surface.

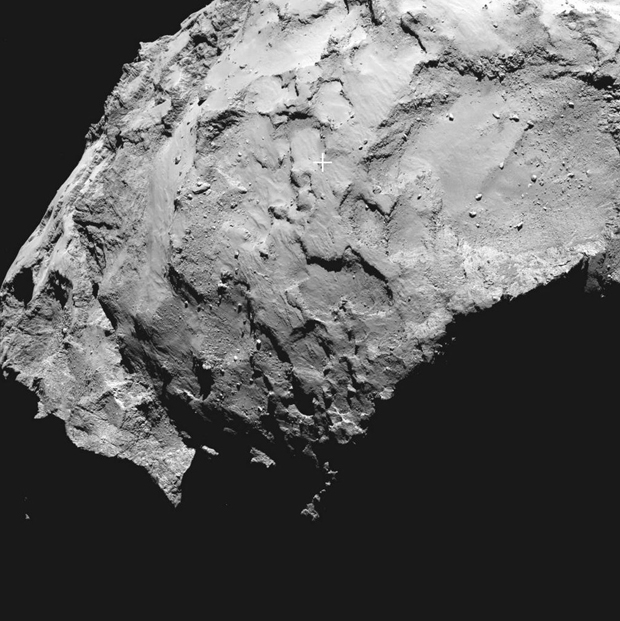

Because of the strange, dual-lobe shape of the slowly rotating comet, picking a landing site was no easy task given the widespread presence of boulders, steep slopes, pits and sharp cliffs that define the comet's remarkably varied surface. Not to mention the possible effects of icy jets of gas and dust that may evolve nearby as the comet warms up.

"The comet is an active body, there is gas flowing out, there is dust flowing out, there is gravity, not a lot, but enough to distort the spacecraft in its path, and we really have to learn how to optimally maneuver," said European Space Agency mission manager Fred Jansen.

"Because at the end of the day, when you're at a distance of 10 kilometers, you can't make big mistakes. You really have to be accurate."

Going into the mission, long before anyone knew what to expect at 67P, the odds of a successful landing were thought to be somewhere between 70 and 75 percent. But that was assuming a relatively smooth landing site on a much more uniform comet. It's not clear what the odds are now that the actual comet has revealed itself, but mission planners are doing everything possible to maximize the odds of success.

"Originally, we were all thinking that we would get to some kind of rounded, potato-shaped comet with evidently rough and structured terrain," Jansen told reporters Monday. "You will realize that the complicated double-structure of the comet really complicates and has an impact on the overall risk related to landing."

Scientists initially identified five possible landing sites, and Jansen said none of them met all the engineering requirements.

But site J on one end of the smaller of the two lobes making up 67P was the unanimous choice, with a relatively benign landing zone, good lighting for the spacecraft's solar panels and clear lines of sight to transmit data to the Rosetta mothership for relay back to Earth.

"There is not much time and full risk analysis cannot be repeated at this point in time," Jansen said. "What we're focusing on is to actually optimize all our processes, select the best possible landing site, which we've announced today, and then we go into operations and do our very best to make sure we have the best possible strategy to reach the landing site."

When Philae descends to 67P's nucleus in November, on-board cameras will document the journey, followed by a 360-degree stereo panorama from the surface and then closeup views of rocks and soil near the lander using a microscope.

"We're then going to have a number of little laboratory experiments that will measure the gas and the dust, the organic material and the plasma coming away," Mark McCaughrean, senior scientific advisor with ESA's Directorate of Science and Robotic Exploration, said last month.

"And then we're actually going to drill beneath the surface to look at material just under the surface and melt some of that material, we'll dig (it) up and bring into the spacecraft."

The flight plan calls for Rosetta to observe 67P/Churyumov-Gerasimenko through December 2015, monitoring the rise and fall of the comet's activity as it makes its closest approach to the sun in August 2015 and and then heads back out to deep space.

But the upcoming landing is the focus of mission planning in the near term.

"The science planning process for the next few months is a real challenging one," Jansen said. "We have to deal with all the possible choices that can be made, which are a significant number. There are still quite a few (decision points) to come."

But he said the $1.7 billion Rosetta mission already is a major success.

"We're flying at 55,000 kilometers per hour (34,100 mph), 30 kilometers (31 miles) next to a comet," Jansen said. "This is an absolutely unique achievement, and lots of science has already come out of the mission."